~Some Brief Thoughts after the ICML ‘25 Interpretability Workshop~

I have told many people multiple times that I will write a blog post and I keep not ending up with my words written down on a website. I have recently been advised that if I just write down my first thoughts without any attempts to perfect it, there is a much greater chance that words end up being published online. Accordingly, I will take this opportunity to give my personal and subjective experience of the “Actionable Interpretability” workshop at ICML 2025 and then just connect my thoughts with some of the larger trends in the field of interpretability.

I want to start off, however, with the end of this workshop, which had a panel like most. In one of the questions, the panel was asked:

Given that non-interpretability researchers often consider interpretability not that useful, how can we make our interpretability research more interesting to other fields, especially CV/NLP? In other words, are there interesting high-level directions which would allow us to better show the utility of our research?

One of the panelists gave the rather facetious answer that there was no need to convince anyone to join interpretability and that if you didn’t believe in the scientific understanding which interpretability promises, then “go add more GPUs or something”. This was of course met with a round of applause by the audience, before every panelist admitted it was more nuanced than that.

In this blog, I want to dig into that point a little harder, especially since the point of this year’s workshop was specifically designed to focus on the “actionability” of interpretability research, which seems to be in direct contradiction with this opinion.

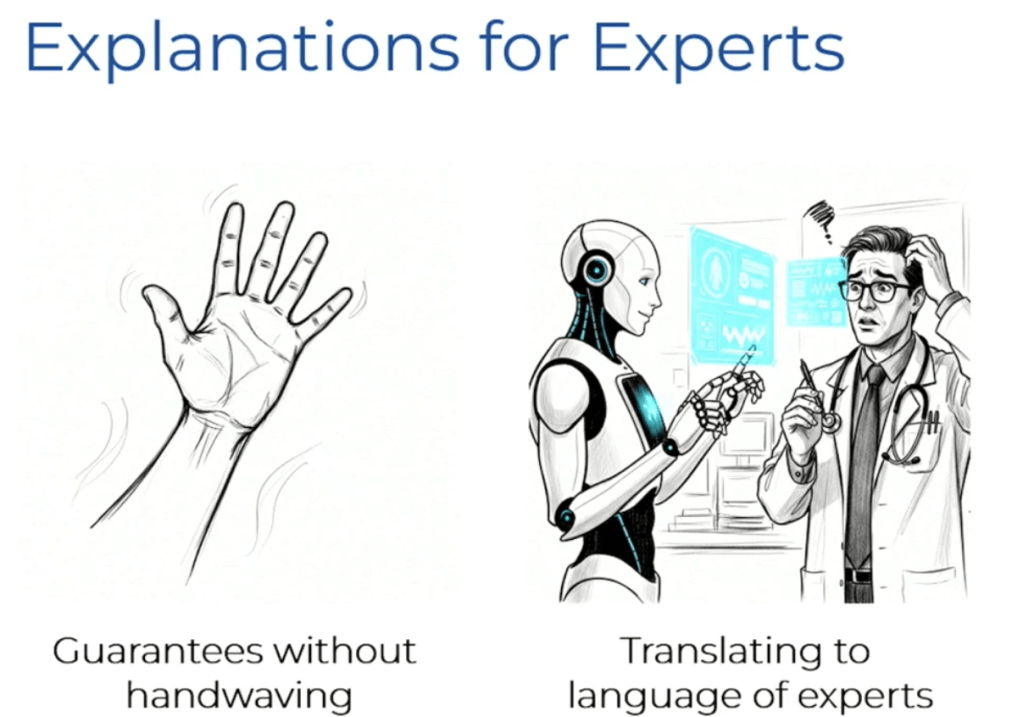

In order to do this, I want to first bring up the recent direction pushed by Been Kim, an incredibly famous interpretability researcher and the opening talk of this workshop. She has recently pushed the direction of considering the “M” space of machine understanding and the “H” space of human understanding.

I think this is a very helpful framework to emphasize the goal of interpretability. In particular, there are some points inside of the “M – H” space which the machine ‘knows’ but the human does not. It is then the goal of interpretability to bring those points into the collective human understanding. This is exactly aligned with the goals of science.

In this most recent talk, Been Kim further stated that the direction going from M to H is what we would call “interpretability”, whereas the opposite goal of bringing the machine’s representation closer to a human understanding would be better called “controllability”, the most famous examples being the alignment problem and safety alignment problems.

It is in this framework, we can begin to see hints of actionability emerging. In particular, it is clear that controllability is one of these possible “downstream actions” which were the focus of the workshop. This is especially the case given that it is the motivation of many of the new researchers in interpretability (many of whom are inspired by mechanistic interpretability which is itself often motivated by the alignment problem). I feel it is accordingly worth trying to emphasize in this blog post how this differs from previous interpretability literature, to be able to distinguish these different motivations in subpopulations of the interpretability community, and to further understand how that leads to varying degrees of actionability. In particular, I believe this alignment motivation directly contrasts itself with what were the more classical downstream tasks of interpretability.

I, myself, work on generalized additive models (GAMs) for tabular datasets. Since I often work on them from a theoretical perspective, frankly, I often do not care at all about the actual actionability considerations. This is in spite of the fact that these actionability questions are something very dear to me. Note that these actions are less in the sort of ‘immediate action’ sense which was implied by this workshop, but more of the ‘exploratory data analysis’ sense which teases out problems as they arise.

For example, the largest applicability of additive models currently is in all likelihood the intelligible healthcare research spearheaded by Rich Caruana. Here the interpretable GAM model is able to detect some concerning trend like asthma patients being low risk for pneumonia mortality (a correlation rather than a causation). This is an absolutely critical insight into the medical dataset; moreover, I do not believe it is straightforward to automate these kinds of insights from the medical professional who helps interpret the GAM model. In fact, I believe this lack of experts is exactly the driving force behind lack of actionability in classical interpretability.

The final invited talk of the workshop, given by Eric Wong, explored exactly these kinds of classical downstream tasks, focusing on his collaborations with two experts in astronomy and three experts in healthcare. The specific applications he presented on were universe simulation with the detection of voids and clusters for cosmological constant prediction, and robust explaining and labeling of gallbladder surgery video for live surgeon assistance. It is my impression that it is hard to overstate the value of these expert collaborators in enhancing the actionability of Professor Wong’s research. Although other interpretability researchers may learn the actionability for these specific tasks from his papers associated with the talk, developing new actionability directions would require experts much like the collaborators of Prof. Wong.

It is for these reasons I wish to emphasize what I think is the great importance of experts for being able to focus on the “actionability” of interpretability, a topic I felt was critically underemphasized in the discussions at this workshop. To then summarize my rather strong opinions on this into three parts:

(a) Theoretical interpretability research is nowhere near done yet. Although the field of (additive) feature attribution has reached a level of maturity not yet seen in other interpretability subfields, there is still a lot of work to be done, including in other areas like axiomatization of mechanistic interpretations and development of sufficiency in explainability. This can be done without an immediate access to experts or need for actionability, even if those considerations should linger in the background.

(b) Mechanistic interpretability also avoids the access-to-experts problem, since many researchers are themselves both the interpretability researcher and the DL/AI expert. However, mech interp has not yet proven itself as the most effective approach for solving the alignment problem, which it is often proposed to solve. In my understanding, safety alignment is still done with RLHF, red-teaming, and fine-tuning (all of which do not explicitly require interpretability).

(c) If actionability really is the necessary shift of priorities for the field of interpretability, and not a shallow attempt by AI/LLM companies to get PhD students working on solving the safety alignment problem for them, then the actual roadblock to achieving actionability is the lack of access to experts. This is true both of classical actionability, where domain experts must confirm or refuse the scientific hypotheses proposed by the model and interpretation in tandem, but also of modern controllability (alignment), where AI researchers working on state-of-the-art LLMs must communicate what their most pressing safety challenges are and what techniques are finding the greatest success in resolving them. Getting scientific experts and deep learning experts to the table is a challenging problem, because you, the interpretability researcher, are asking them to spend and often waste their valuable time to understand the blackbox garbage coming from your model. Nevertheless, if actionability needs to be the goal for a larger subset of interpretability researchers, then I believe this is perhaps the most pertinent issue which must be collectively addressed. Paraphrasing Eric Wong, “You cannot do interpretability research on AI if you need to spend time convincing your expert that what you are doing is valuable.”

Going back to the original question posed to the panelists, let’s review the answers they gave:

- The third panelist, introduced as representing the ‘outsider’ to the interpretability community, pushed back on the notion that only doing science is a good enough motivation and that the interpretability community should listen to outsiders for promoting better usefulness. (Unfortunately, the irony of this claim was not noted by the panelist himself or others.) Although not mentioned in his response here, he had earlier emphasized how XAI techniques can be viewed as metrics for tracking the health of a deep learning model during a training run.

- Another one of the panelists, the one representative of the mechanistic community, was seemingly unable to name any motivations or downstream tasks outside of safety alignment, even when asked explicitly by the moderator to do so. When reminded of this point, he pointed to a (in my opinion tenuous) connection that DNA is a long sequence of text which we don’t fully understand and that (long) chain-of-thought is a long sequence of text that we don’t fully understand.

- The first panelist later refined her position that the goal of interpretability is explicitly trying to ‘wrestle back’ the scientific understanding which we have given away to large blackbox models in the first place. Although much of the audience can probably imagine some explicit applications across scientific domains, still no explicit directions were mentioned.

- And finally, the last panelist then mentioned how there is just no “real need” for interpretability in many of these different domains, simply causing a mismatch in incentives. In nearly every domain outside of discovery, there is no requirement for an understanding or an explanation, making the point that you don’t “make more money” by adding interpretability in these domains (in fact you often make yourself susceptible to further critiques on fairness or accountability).

In my impression, all of these answers, while good, were still relatively devoid of concrete examples that could be worth working on. Accordingly, I feel like these four answers are already more than enough to demonstrate not only the differences in motivations for researchers across the field (and thus what is even meant by “actionability”), but also to the challenging nature of the problem itself. There was a single point of consensus, however, which was that the best way to achieve actionable insights on downstream tasks is to start trying in the first place.

So, to the question as it was originally asked, “how do we make interpretability research useful for CV/ NLP?”, I think the answer is that we simply don’t know. It is for this reason many researchers inside the field are so excited about the field as well as why there are so many different subareas of research all approaching the problem from different perspectives. I, too, have heard from many a DL/AI researcher that interpretability is not that useful, and I personally don’t believe we deserve to drop that stigma quite yet. However, to think that interpretability has not made a tremendous amount of progress over the past decade is to be ignorant of the field. Just because there is nothing that quite ‘works’ yet in many CV/NLP applications is not a reason to claim no progress has been made. As Thomas Edison is famously quoted as saying, “I have not failed one thousand times. I have successfully discovered one thousand ways that do not work”.

Leave a comment