~Some Brief Opinions after the NeurIPS ‘25 Interpretability Workshop~

I again wanted to share some thoughts on the field of interpretability, this time under the pretense of responding to the “Mechanistic Interpretability” workshop at NeurIPS 2025. Mostly, I want to discuss the rising tide of mechanistic interpretability and ask the question: Mechanistic? As the title implies, I would like to do so somewhat critically.

Disclaimer: Given the overlap with those interested in mech interp and the ‘LLM-pilled’ or ‘AI bros’, I do want to begin with a bit of disclaimer, one which I hope is not interpreted too harshly but can be understood as a necessary caveat. If you as the reader seriously believe that we will all be subservient slaves to AGI within the next five years, I beg you to stop reading. Go enjoy the time with your friends and family or otherwise prepare as you see fit. I don’t plan to convince you that AGI will not occur in the next five years, and many of my arguments will implicitly depend on the vision that society will not have majorly collapsed in the time being (as most rational arguments tend to).

With that out of the way, the main question I want to ask throughout this blogpost is that of: “Is mechanistic interpretability the most effective pathway for understanding deep neural networks?” As I will eventually get to, I feel that mechanistic interpretability, in its current form, is not going to lead to the major breakthroughs in our understanding of deep learning or large language models which were promised early on, and I believe that one of the main culprits holding back mechanistic interpretability is the culture of its research community.

To even begin such an argument, I first need to say what I mean by mechanistic interpretability. Following the language of Naomi Saphra and Sarah Wiegreffe’s “Mechanistic?”, I will mostly consider mechanistic interpretability in the “broad technical definition” and the “narrow cultural definition”. That means that, technically speaking, I consider mechanistic interpretability as any research looking at model internals, rather than only considering causality-based mechanism understanding; and, culturally speaking, I consider the field of mechanistic interpretability as only encompassing the research from that community, rather than the name for the entirety of natural language interpretability, or even all of interpretability.

Two High-Level Presentations

I want to have this discussion by juxtaposing the opening and closing talks of the workshop. The opening talk was by Been Kim on “15 years of research in interpretability” and the closing talk was by Chris Olah about “reflections on mechanistic interpretability”. But before contrasting them, I want to spend a moment on what I think are some of the major takeaways from these talks by two titans in the field of interpretability.

One of the points made early on in Olah’s talk was about how neural networks are grown not built by way of the inscrutable dynamics of gradient descent. He went on to say how this means we should embrace the biology and empiricism required to study these complex systems. On this point, I heavily agree with him, but I actually feel this is one of the major shortcomings in mechanistic interpretability research at the moment. He then talked about how we should all consider working on ‘ambitious interpretability’, but can balance this out with applied LLM safety projects (presumably because this is the only application he is aware of). I also find this to be a laudable goal.

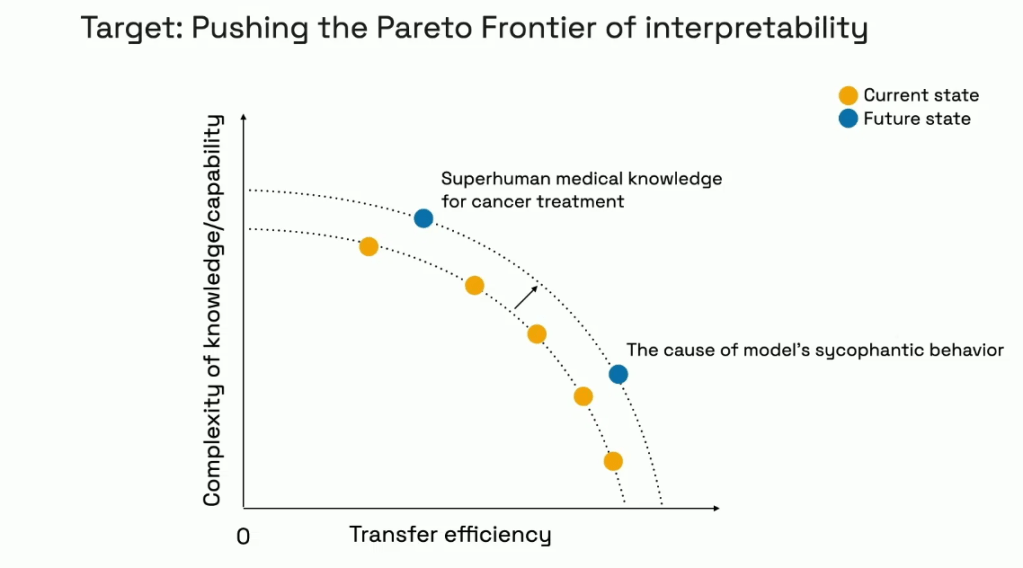

In Kim’s talk, the major idea she was building towards was the idea of the Pareto frontier of interpretability. Her goal is still about extracting AI insight for human understanding, as in what she has previously called neology or what David Bau would call the empowerment view. The purpose is to be able to transfer some superhuman knowledge from the AI to the human, with the two axes of the Pareto frontier being the “complexity of the transferred knowledge” and the “transfer efficiency”, which is defined as the improvement in human performance (seemingly a proxy for knowledge learned) per time taken. It seems the choice to put ‘transfer speed’ rather than the (inverse) ‘time taken’ is to emphasize the practical utility for a single user, rather than emphasizing its use as a tool for scientific discovery for human kind. She writes more about this in a blog post here.

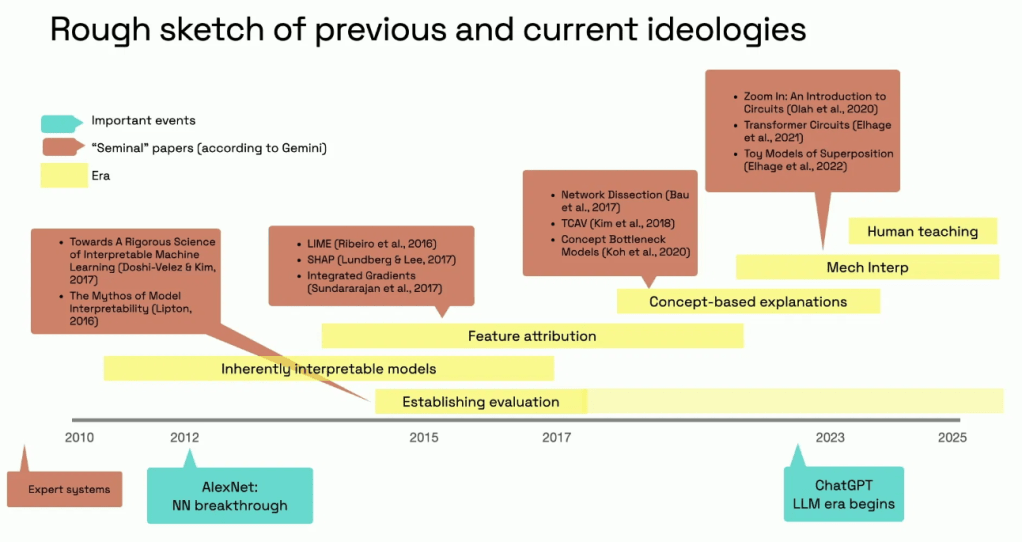

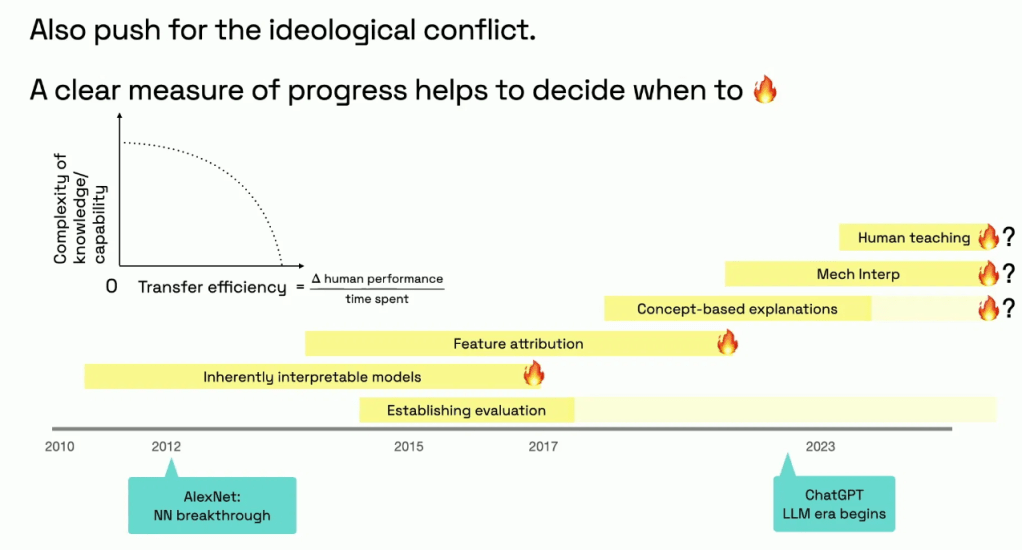

The way she built up to this was via a whirlwind tour through the history of interpretability. She talked about some of the main areas as being: inherently interpretable methods, feature attribution, concept-based explanations, and mechanistic interpretability. Throughout the discussion, she emphasized the importance of evaluation and the natural gullibility of researchers. There is a fundamental conflict between the interpretability researcher, who wants their method to succeed, and the interpretability research, which needs to be thoroughly verifiable. She pointed out how for inherently interpretable models and feature attributions, fundamental limitations are already well established in research papers (e.g. sanity checks).

Although due to my research background I don’t agree that those subfields have stopped making progress, it is fair to say that those earliest forms cannot be scaled up even to the level of the 2016 ResNet, one of the earliest forms of real deep learning, and already at this point 10 years old. Personally, I believe this is true for all current interpretability. Nonetheless, the major point she was making is that “we fooled ourselves into believing that we understand something, and this is a lurking danger prominent, still, to this day”.

With that in mind, I will say the quiet part out loud. Concept-based explanations, and especially mechanistic interpretability, have never gone through the same rigorization that these other subareas of interpretability have been forced to by facing a wave of evaluation. As it stands right now, there are no parallel ways for interpretability researchers to validate/ evaluate whether or not their discovered concepts or uncovered mechanisms are truly reflected in the model. It is my view that this is in part the responsibility of the culture of mechanistic interpretability, which seems insofar to overemphasize hype and affirmations, and to avoid critical and condemnatory language.

Accordingly, I think Olah has already fallen victim to what in the end of his talk he called the ‘advocacy trap’, where people can “lose credibility by… advocating a position [which] in the long-run undermines scientists”. The culture of hype for mechanistic interpretability has insulated the field from (a) building upon existing interpretability tools; and from (b) scientific criticism coming from outside of the community. I think it could be said that interpretability is honestly facing the end of its pre-paradigmatic era, and I think there are many researchers who ought to start acting like it.

To continue to tell the next generation of interpretability researchers that if they spend enough time tinkering with LLM safety applications, that they will suddenly grok a complete understanding of the deep and complex structure in language models… I think it is not a very productive approach. It might be time to really take stock on what mechanistic interpretability has delivered in the past several years, and how to actually measure those findings and verify those tools.

Two High-Level Blogposts

Another two pieces which were definitely part of the zeitgeist of this workshop were the GDM blogpost about “pragmatic interpretability” by Neel Nanda and others, as well as the (requested) response blogpost from researcher David Bau titled “In Defense of Curiosity”.

Although I cannot read the GDM blogpost in full due to its writing style, it seems to follow up on GDM’s post earlier in March of the same year (2025) claiming they will deprioritize their main approach of SAE-based mechanistic interpretability. The major points they make in their most recent post are that: (1) researchers should only choose problems where simple methods outside of interpretability have already failed, and (2) that there is a need for empirical feedback on downstream tasks. On this second point, I think every interpretability researcher already knows that evaluation is the most critical and most difficult part of every project. In that sense, I think writing an entire blogpost to make such a point is a little crude, but perhaps it is justified under the view that mechanistic interpretability is really so insulated from interpretability research. On the former point, I only partially agree. I think mechanistic interpretability researchers are often motivated by safety applications where the goal is to have control over the LLM. In that case, it makes sense to try other simpler approaches before interpretability. Instead, I am often motivated by the potential of interpretability for scientific discovery and understanding, where it is perhaps already clear that interpretability is required. I have written on these two somewhat antithetical positions before in a blog post.

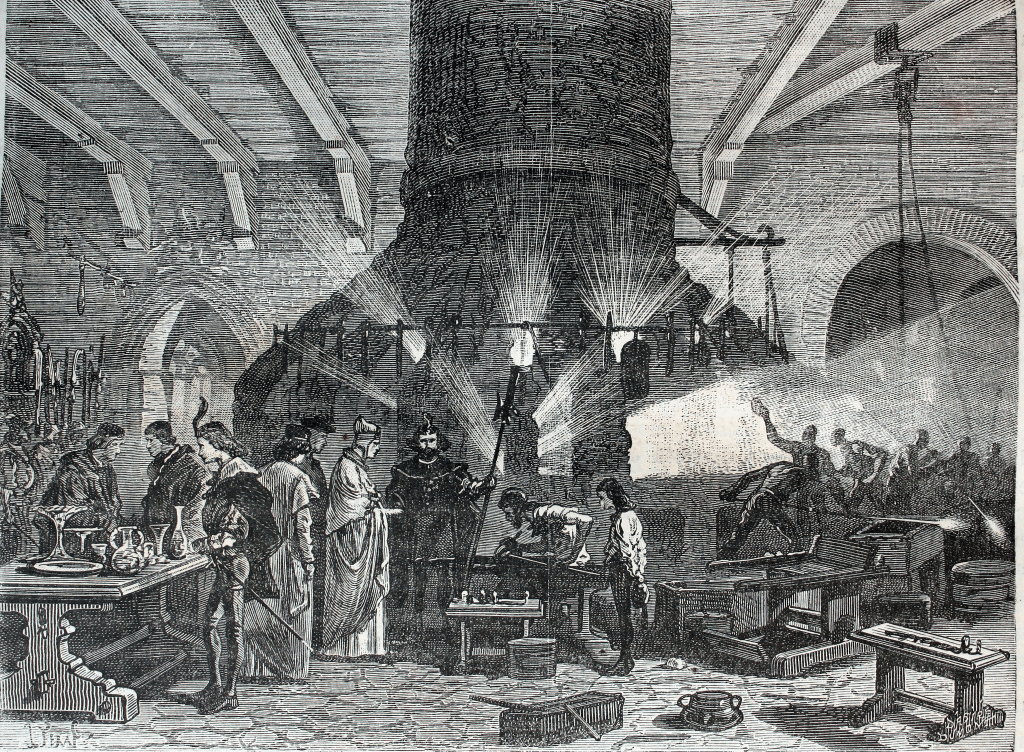

In Bau’s blogpost (which also had a short spoken version during lightning talks, 46:04), he tells a quick story about glassmaking. He compares pragmatic interpretability to the difference between Venetian glassmaking for art and the ‘pragmatic glassmaking’ of creating spectacles. Of course this was an incredibly useful vocation which allowed many people to read with greater ease. Nevertheless, it was their later development into telescopes and Galileo’s curious decision to point them at the sky which fueled the Copernican Revolution.

He then suggests there are three main motivations for doing interpretability research: 1. the adversarial view; 2. the empowerment view; and 3. the scientific view. The adversarial view is about detecting when LLMs’ internal thoughts don’t match their outputs, hence it is the most pragmatic and tied to safety applications. The empowerment view is the same as most interpretability researcher’s hunger for understanding what the AI knows that humans can’t yet understand, exactly in the same sense as Been Kim mentioned above. Lastly, the scientific view is about how to use LLMs as a model of rational thinking, something which has never been possible outside of other animals (where he parallels the human-centric prescription of consciousness to the geocentric prescription of the solar system).

On these different views, he claims that to him the second view is the most important and the third view is the most underappreciated, neither of which being the pragmatic first view. On the first view being not so important, I agree, but I think this statement runs counter to a large swath of mechanistic interpretability researchers who are subconsciously motivated by AI safety applications. On the second view being the most important, I again agree this is the fundamental spirit of interpretability research. On the third view being underappreciated, it is my view that this is exactly what people are asking for when they are asking for us to embrace the biology and the neuroscience of mechanistic interpretability. But both the culture and the expertise of computer science researchers have restricted us from embracing the experimentalist culture ingrained into the life sciences and have precluded us from curiously asking the right questions. Fundamental better understanding in this third direction is perhaps the key scaffolding needed to better support the other two directions.

Concluding Thoughts

In summary, it is my view that the current culture of mechanistic interpretability has prevented it from embracing the teachings of the decade-old field of interpretability and has insulated it from facing the criticisms necessary for advancement. Someone I was talking to mentioned that they thought Olah’s talk seemed “ominously distant”, especially with respect to his decision against giving any concrete ideas to work on. Similarly, Nanda’s blogpost seems like a curious vaguepost which could be translated to ‘what we have been trying has completely failed’. From my perspective as an outsider to the field, these read like signals that the flagbearers of mechanistic interpretability are ready to admit that they don’t know which direction to go.

That being said, as someone with ‘no skin in the game’ of mechanistic interpretability, I certainly can’t be the one to throw in the towel for the field. Nevertheless, from an outside perspective, it seems like we are closing in on the end of the ‘age of tinkering’, where researchers are being caught up to by the consequences of wishy-washy research practices. With all that finally said, I also don’t want this to come off as a blanket attack on every researcher who considers themself as working on mechanistic interpretability. Culture failings are not universal across every researcher in the field, and I am only talking about the most vocal and dominant sentiment which I get exposed to as someone working outside the field.

In contrast, I do believe in a biological understanding of artificial intelligence; I do believe in the long-term goals of ambitious interpretability; and, especially, I believe in the need for curiosity. An increasing number of people I talk to are no longer believing that it will ever be possible to understand ChatGPT 3.5 in full detail; however, if we convince everyone that it isn’t possible, then of course humanity would never succeed here. But, that’s not how scientific progress is made. I have never believed that one tinkering engineer would be able to solve such a challenging problem, and I don’t believe it now. I believe such ambitious goals need a large helping of curiosity alongside a healthy dose of measured criticism in order to make serious progress in a serious field.

Leave a comment